Last week the House of Lords decided to end the printing of laws on vellum for cost reasons. But now the Cabinet Office is to provide the money from its own budget for the thousand-year-old tradition to continue.

Vellum lasts a long time. Dig into the archives of the UK's parliament and pull out the oldest extant law and you'll find a very old document. It was first inscribed in 1497.

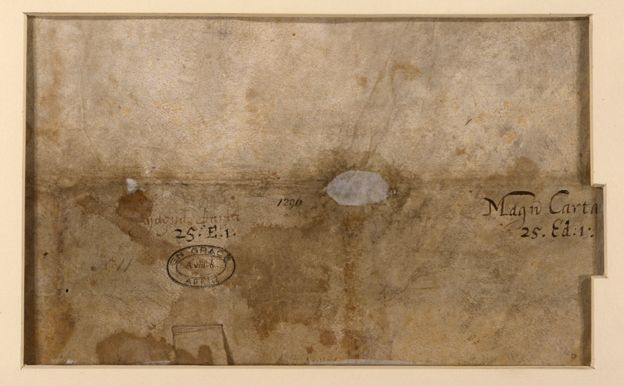

Over time, ordinary paper can deteriorate rapidly, while vellum is said to retain its integrity for much longer. Original copies of the Magna Carta, signed more than 800 years ago on vellum, still exist.

The proposed change was a move to higher-quality archival paper. But are politicians missing the point

"We simply respond to the way parliament chooses to create its records," Brown says. "In this case those are still going to be physical - though the proportion that is digital will increase over time."

But there are other reasons, too.

Sharon McMeekin, of the Digital Preservation Coalition, an advocacy and advice group for digital recordkeeping, thinks so.

"People have been bemoaning the loss of history by changing to archival paper," she explains. "I think people are missing the point there. Truly representing the context and history in which these records were made require them to be kept in a digital format. It's more representative of the technologies and communication methods used today."

So why in the digital age do we keep physical records of documents at all?

There's a simple answer, says Adrian Brown, the director of parliamentary archives, who oversees a collection including 8km-worth of physical records of parchment, paper and photographs in the 325ft tall Victoria Tower at the western edge of the Palace of Westminster.

In the tower, scrolls of vellum are piled up in a vast repository, spooled in a range of different sizes, looking superficially much as they would have done hundreds of years ago.

"In many circles there's still a real discomfort around digital archiving, and a lack of belief that digital can survive into the future," explains Jenny Mitcham, digital archivist at the Borthwick Institute for Archives at the University of York.

The whole concept of digital storage is a relatively new innovation, and the path by which it could survive through the years is not clear.

"We don't have the ability to look back and say we know for a fact in 200 years time we'll still have this stuff," reasons Mitcham. "We can't prove that fact without a time machine."